Suspended Cities *01

... ‘the mere thought of “you need a new flat” is something so cruel these days that people can no longer even dream of a really new form of housing. Because the problem of housing is not only a problem of social organisation and therefore - this is the consequence today - a problem of the greatest possible mobility.’ 1

These words by Conrad Roland from the 1960s could just as easily describe the current housing crisis. Housing is becoming increasingly scarce, rents and property prices continue to rise - a move is becoming an adventure. Anyone who has an affordable home can consider themselves lucky and, if at all possible, will not give it up lightly. The result? Deserted neighbourhoods of single-family homes where the remaining residents age and empty children's rooms are left behind, while young families in the cities fight for every square metre of living space. Then as now, this was a dilemma and an urgent social issue, because:

‘What does marriage mean, the first child, the second, the third? What does it mean to have a relative in need of care who refuses to be relocated? What does it mean when the children get older, but then move out one by one when said relative dies? Each time: a flat that is too small, too big or - a new one!’ 2

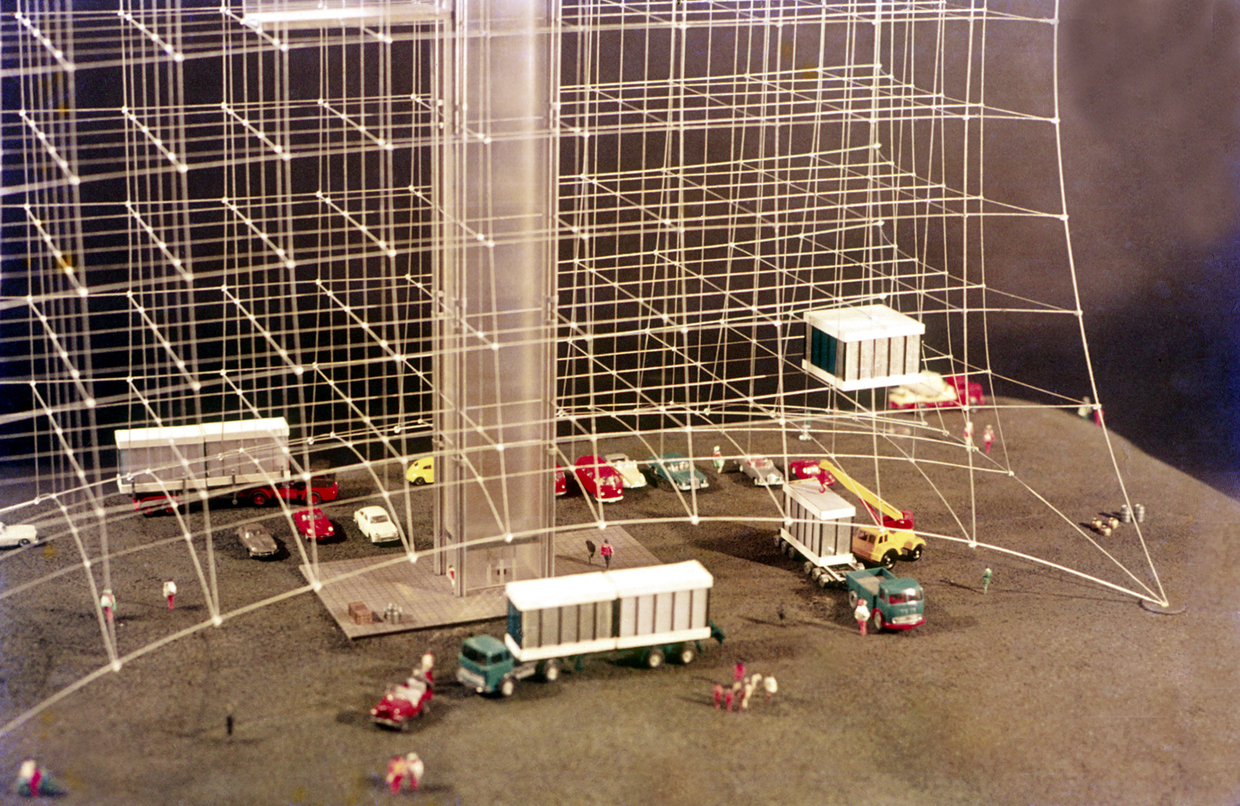

With this exaggeration, Roland was primarily criticising a housing policy that meant that flats, like ‘rigid cages’, could not be adapted to ‘changing needs or only with great effort’. 3 His radical counter concept: a constantly variable spatial city with modular living elements, suspended in huge cable net constructions that were to be light, adaptable and mobile.

‘We would move studios and offices away from the flats, growing children would not have to sit irritably with their parents for years, the misery of subtenants would disappear by itself, the catastrophic sociological structure of our individual blocks of flats - here old people's homes or chic apartment blocks with bachelors, single ladies and widowed, still sprightly grannies, there inadequate, poor social housing, crammed to the rafters with children - all that would be gone.’ 4

His ideas were born in an inspiring environment, characterised by lively discussions ‘about the future not only of architecture, but of the entire way of life in the cities of the next fifty years.’ 5 After studying at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago under Ludwig Hilberseimer and working in Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's office, Roland had returned to Germany from the USA and from 1961 worked in Berlin with Frei Otto on a paper on ‘Tension Structures for Multi-storey Buildings’ 6. Fascinated by Otto's delicate supporting structures, Conrad Roland developed concepts for large-scale suspended cities in order to ‘free society from the straitjacket of architecture’. 7 In a personal letter to his father, he enthused about buildings ‘that will be as beautiful and alive as a spider's web, like a tree, buildings that will grow, be filled with life and perhaps be transformed again decades later, fade away’. 8

The architect and visionary was ahead of his time in many respects with his designs: without explicitly naming it, he addressed issues such as resource consumption, circular building, land consumption and sealing in addition to adaptability to the changing spatial needs of residents - issues that are among the central global discussions today. His dynamic structures were not only intended to be aesthetically pleasing and maximise flexibility of use, but also require minimal use of materials. He also envisaged spanning existing traffic areas such as railway tracks, highways or canals and being able to dismantle them without leaving any residue if necessary.

Götz Aly, historian, political historian and journalist, significantly subtitled his newspaper article ‘Castles in the air in the space net’ about the architectural ideas of his brother-in-law Conrad Roland ‘Living tomorrow - an example of a realisable utopia’. In doing so, he expressed how convinced he was not only of the theoretical potential of these designs, but also of their practical realisability. At the time, neither Roland nor Aly had any idea that these visionary constructions would ultimately take shape - on a transformed scale - in the playgrounds of this world.

MG, 15.12.2024

1 Götz Haydar Aly: Example of utopian living concepts. Fertigbau, Fachzeitschrift für industrialisiertes Bauen, 6. Jahrgang, Heft 8, August 1969, S. 4–7f.

2 Ebd.

3 Götz Haydar Aly: Luftschlösser im Netz. Wohnen morgen - Beispiel einer realisierbaren Utopie. Junge Stimme (Wochenzeitung, Stuttgart), 18.Jahrg., 10. Mai 1969, S.5.

4 Aly (1969): Example of utopian living concepts.

5 Letter from Conrad Roland to his father, undated.

6 „Mitteilung Nr. 8“ from the publication series of Entwicklungsstätte für Leichtbau.

7 Aly (1969): Example of utopian living concepts.