Spielraumnetze *03

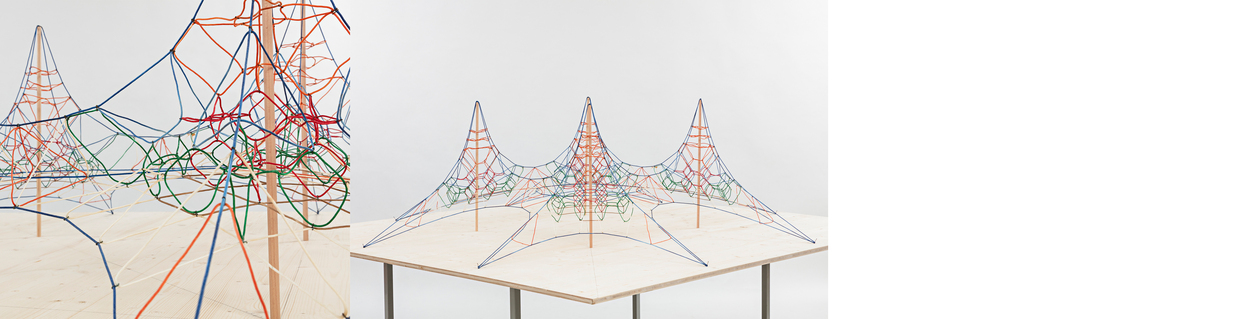

An archive is not a place of stagnation. It preserves not only objects, but also the knowledge inscribed in them. For this reason, the original rope-net models by architect Conrad Roland should not remain stored in zip-lock bags, but be reactivated. As part of a one-day workshop held in the photographic studio of the KIT Faculty of Architecture, several models from Roland’s estate were reconstructed. During their assembly, the models’ structural, material and spatial qualities could be grasped directly, through hands-on engagement rather than abstract description. Above all, it became evident how much implicit knowledge is embedded in these objects. The reconstruction was accompanied by Torsten Frank, Senior Technical Advisor at the playground equipment manufacturer KOMPAN, that continues to develop and distribute Roland’s net concepts to this day. His experiential knowledge proved essential in retracing design principles that cannot be inferred from documents alone.

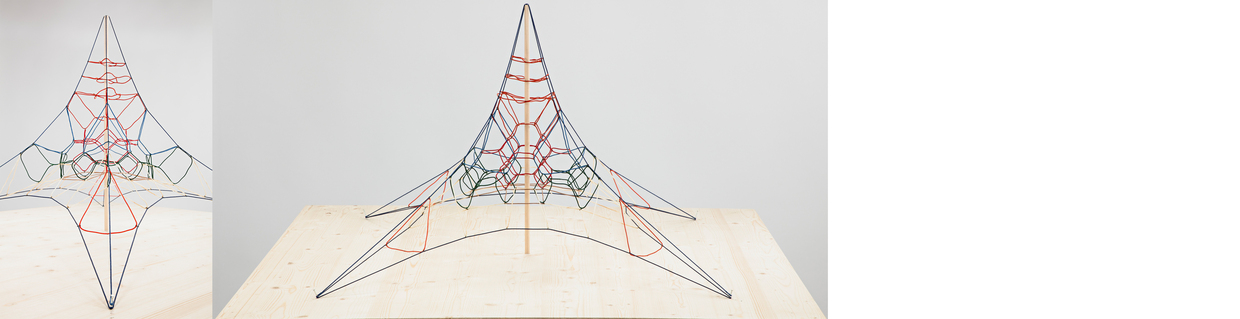

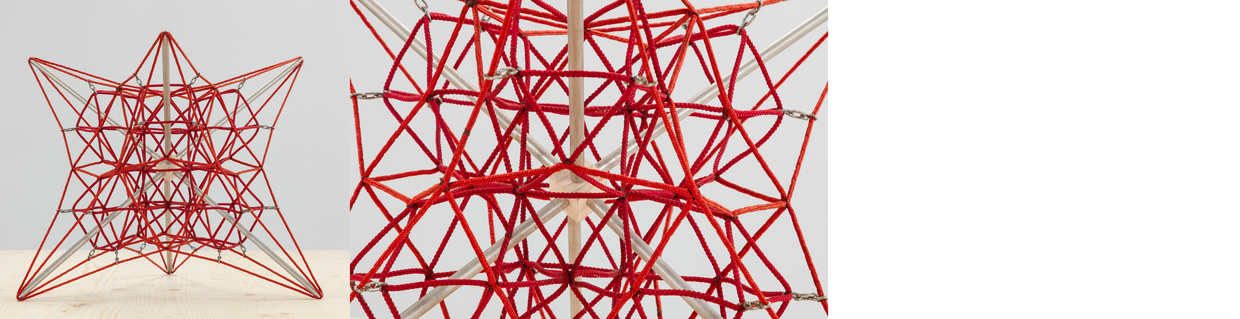

Roland worked extensively with models. For him, they were tools for thinking: instruments for generating ideas, testing structural systems and assessing spatial effects. He moved fluidly between scales, ranging from 1:1 student-built prototypes and abstract geometric studies to large-scale presentation models. For him, experimenting with different scales was a design method—one that departed from the linear logic of concept, detailed design and construction. Over many years, Roland continuously developed his projects, scaling, recombining and transferring them into new contexts—from utopian hanging cities to the later spatial play nets. This dynamic became tangible during the workshop. Shifting individual nodes or re-tensioning a single rope immediately revealed how closely stability, flexibility and spatial perception are intertwined. What remains abstract in drawings becomes concrete in the model—and demands decisions.

The work on the models was comprehensively documented, both in the form of an inventory and through observation of the creation process. The finished models were professionally recorded from multiple perspectives, including detailed views. This systematic survey in the sense of cataloguing facilitates scientific access to the objects for research purposes. At the same time, the assembly process itself was documented photographically and on film: the repeated tensioning and loosening of ropes, the setting of new nails, the careful search for correct distances. It is precisely in these moments that the craft-based knowledge required to ensure both spatial quality and structural performance becomes visible. Only the interplay between the development process and the end result makes it possible to understand, review and, if necessary, reapply Roland’s approach.

The reconstruction also provided important insights into the long-term preservation of the up to 40-year-old models made of Perlon cord (polyamide). In order to take on their characteristic shape, they must be stretched tightly. Polyamide is hygroscopic. The humid summer conditions during the workshop therefore proved advantageous, as the material could be stretched more easily and retained its form for a limited period of time. Based on these observations, a new storage concept was developed. Instead of being tightly compressed in bags and boxes, the nets will in future be stored in a stretched state—softly padded, breathable, and housed in custom-made archival boxes.

Such reenactment goes far beyond the mere conservation of archival material. The documentation enriches the estate with forms of practical, process-based knowledge that would otherwise be lost. It demonstrates that a work archive is not a static repository, but a dynamic system in which knowledge emerges through active engagement with material objects. The reconstruction thus forges a bridge between archive and present. Working with the models is not only a retrospective act, but also a methodological step forward—securing process knowledge as a long-term resource for research.

MG, ME, 12.12.2025